Tor.com is honored to reprint “St. Dymphna’s School For Poison Girls,” a short story by Angela Slatter originally appearing in The Bitterwood Bible, available from Tartarus Press, with pen-and-ink illustrations by artist Kathleen Jennings.

The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings returns to the world of Slatter’s Sourdough and Other Stories, introducing readers to the tales that came before. Stories where coffin-makers work hard to keep the dead beneath; where a plague maiden steals away the children of an ungrateful village; where poison girls are schooled in the art of assassination; where pirates disappear from the seas; where families and the ties that bind them can both ruin and resurrect and where books carry forth fairy tales, forbidden knowledge and dangerous secrets.

St Dymphna’s School for Poison Girls

‘They say Lady Isabella Carew, née Abingdon, was married for twenty-two years before she took her revenge,’ breathes Serafine. Ever since we were collected, she, Adia and Veronica have been trading stories of those who went before us—the closer we get to our destination, the faster they come.

Veronica takes up the thread. ‘It’s true! She murdered her own son—her only child!—on the eve of his twenty-first birthday, to wipe out the line and avenge a two-hundred year old slight by the Carews to the Abingdons.’

Adia continues, ‘She went to the gallows, head held high, spirit unbowed, for she had done her duty by her family, and her name.’

On this long carriage journey I have heard many such recountings, of matrimony and murder, and filed them away for recording later on when I am alone, for they will greatly enrich the Books of Lives at the Citadel. The Countess of Malden who poisoned all forty-seven of her in-laws at a single banquet. The Dowager of Rosebery, who burned the ancestral home of her enemies to the ground, before jumping from the sea cliffs rather than submit to trial by her lessers. The Marquise of Angel Down, who lured her father-in-law to one of the castle dungeons and locked him in, leaving him to starve to death—when he was finally found, he’d chewed on his own arm, the teeth marks dreadful to behold. Such have been the bedtime tales of my companions’ lives; their heroines affix heads to the ground with spikes, serve tainted broth to children, move quietly among their marriage-kin, waiting for the right moment to strike. I have no such anecdotes to tell.The carriage slows as we pass through Alder’s Well, which is small and neat, perhaps thirty houses of varied size, pomp, and prosperity. None is a hovel. It seems life for even the lowest on the social rung here is not mean—that St Dymphna’s, a fine finishing school for young ladies as far as the world-at-large is concerned, has brought prosperity. There is a pretty wooden church with gravestones dotting its yard, two or three respectable mausoleums, and all surrounded by a moss-encrusted stone wall. Smoke from the smithy’s forge floats against the late afternoon sky. There is a market square and I can divine shingles outside shops: a butcher, a baker, a seamstress, an apothecary. Next we rumble past an ostlery, which seems to bustle, then a tiny school house bereft of children at this hour. So much to take in but I know I miss most of the details for I am tired. The coachman whips up the horses now we are through the hamlet.

I’m about to lean back against the uncomfortable leather seat when I catch sight of it—the well for which the place is named. I should think more on it, for it’s the thing, the thing connected to my true purpose, but I am distracted by the tree beside it: I think I see a man. He stands, cruciform, against the alder trunk, arms stretched along branches, held in place with vines, which may be mistletoe. Green barbs and braces and ropes, not just holding him upright, but breaching his flesh, moving through his skin, making merry with his limbs, melding with muscles and veins. His head is cocked to one side, eyes closed, then open, then closed again. I blink and all is gone, there is just the tree alone, strangled by devil’s fuge.

My comrades have taken no notice of our surrounds, but continue to chatter amongst themselves. Adia and Serafine worry at the pintucks of their grey blouses, rearrange the folds of their long charcoal skirts, check that their buttoned black boots are polished to a high shine. Sweet-faced Veronica turns to me and reties the thin forest green ribbon encircling my collar, trying to make it sit flat, trying to make it neat and perfect. But, with our acquaintance so short, she cannot yet know that I defy tidiness: a freshly pressed shirt, skirt or dress coming near me will develop wrinkles in the blink of an eye; a clean apron will attract smudges and stains as soon as it is tied about my waist; a shoe, having barely touched my foot, will scuff itself and a beribboned sandal will snap its straps as soon as look at me. My hair is a mass of—well, not even curls, but waves, awkward, thick, choppy, rebellious waves of deepest fox-red that will consent to brushing once a week and no more, lest it turn into a halo of frizz. I suspect it never really recovered from being shaved off for the weaving of Mother’s shroud; I seem to recall before then it was quite tame, quite straight. And, despite my best efforts, beneath my nails can still be seen the half-moons of indigo ink I mixed for the marginalia Mater Friðuswith needed done before I left. It will fade, but slowly.

The carriage gives a bump and a thump as it pulls off the packed earth of the main road and takes to a trail barely discernible through over-long grass. It almost interrupts Adia in her telling of the new bride who, so anxious to be done with her duty, plunged one of her pearl-tipped, steel-reinforced veil-pins into her new husband’s heart before ‘Volo’ had barely left his lips. The wheels might protest at water-filled ruts, large stones and the like in their path, but the driver knows this thoroughfare well despite its camouflage; he directs the nimble horses to swerve so they avoid any obstacles. On both sides, the trees rushing past are many and dense. It is seems a painfully long time before the house shows itself as we take the curved drive at increased speed, as if the coachman is determined to tip us all out as soon as possible and get himself back home to Alder’s Well.

St Dymphna’s School (for Poison Girls) is a rather small-looking mansion of grey-yellow granite, largely covered with thick green ivy. The windows with their leadlight panes are free of foliage. The front door is solid, a scarred dark oak—by its design I’d judge it older than the abode, scavenged from somewhere else—banded with weathered copper that reaches across the wood in curlicues.

Our conveyance slews to halt and the aforementioned front door of the house is opened in short order. Three women step forth. One wears a long black dress, a starched and snowy apron pinned to the front; her hair is ash-coloured and pulled back into a thick bun. The other two move in a stately fashion, ladies these, sedate, precise in their dress, fastidious in their person.

Serafine, too impatient to wait for the coachman, throws back the carriage door; she, Adia and Veronica exit eagerly. I pause a moment to collect my battered satchel, hang it across my chest; it puckers my shirt, adds more creases as if they were needed. I pause on the metal footplate to take everything in. There is a manicured lawn, with a contradictory wild garden ranging across it, then a larger park beyond and the forest beyond that. A little thatched cottage, almost completely obscured by shrubs and vines, hides in one corner, a stable not far from it, and the beds are filled with flowers and herbs. A body of water shimmers to the left—more than a pond, but barely a lake—with ducks and geese and elegant swans seemingly painted on its surface.

‘Welcome, welcome, Serafine, Adia, Veronica and Mercia,’ says one of the Misses, either Fidelma or Orla. I climb down and take my place in line with St Dymphna’s newest crop, examining my teachers while I wait for their warm gazes to reach me. Both are dressed in finery not usually associated with school mistresses—the one in a dress of cloth of gold, the other in a frock of silver and emerald brocade—both wearing heavy gold-set baroque pearl earrings, and with great long loops of rough-cut gems twisted several times about their necks. Then again, were they ordinary school mistresses and this nothing but a finishing school, our families would not have gone to such lengths to enrol us here for a year’s special instruction.

‘Welcome, one and all,’ says the other sister, her heavy-lids sweep great thick lashes down to caress her cheek and then lift like a wing, as a smile blossoms, exposing pearly teeth. In her late forties, I’d say, but well-preserved as is her twin: of the same birthing, but not identical, not the same. As they move closer, strolling along the line we’ve formed… ah, yes. She who spoke first is Orla, her left eye blue, the right citrine-bright. Neither short nor tall, both have trim figures, and peach-perfect complexions, but I can see up close that their maquillage is thick, finely porous, a porcelain shell. The cheeks are lightly dusted with pink, the lashes supplemented with kohl and crushed malachite, mouths embellished with a wet-looking red wax. I think if either face were given a swift sharp tap, the masque might fracture and I would see what lies beneath.

How lined is the skin, I wonder, how spotted with age, how thin the drawn-in brows, how furrowed the lips? And the hair, so thick and raven-dark, caught-up in fine braided chignons, shows not a trace of ash, no sign of coarsening or dryness. Their dresses have long sleeves, high necks, so I can examine neither forearms, nor décolletage, nor throats—the first places where Dame Time makes herself at home. The hands, similarly, are covered in fine white cambric gloves, flowers and leaves embroidered on their backs, with tiny seed-pearl buttons to keep them closed.

Orla has stopped before me and is peering intensely, her smile still in evidence, but somehow dimmed. She reaches out and touches a finger to the spot beneath my right eye where the birthmark is shaped like a tiny delicate port-wine teardrop. She traces the outline, then her smiles blooms again. She steps away and allows Fidelma—left eye yellow, right eye blue—to take her place, to examine me while the other students look on, perplexed and put out. Serafine’s lovely face twists with something she cannot control, a jealousy that anyone other than she might be noticed. Orla’s next words offer a backhanded compliment.

‘This,’ she says severely, indicating the tear, ‘this makes your chosen profession a difficult one—it causes you to stand out even more than beauty does. Any beautiful woman might be mistaken for another, and be easily forgotten, but this marking renders you unique. Memorable. Not all of our alumni are intent upon meeting a glorious and swift demise; some wish to live on after their duty is done—so the ability to slip beneath notice is a valuable one.’

I feel as if I have already failed. Adia laughs heartily until quelled by a glance from Fidelma, who says to me, ‘Never fear, we are mistresses of powders and paints; we can show you how to cover this and no one will even suspect it’s there!’

‘Indeed. You were all chosen for virtues other than your lovely faces,’ says Orla, as if our presence here isn’t simply the result of the payment of a hefty fee.

At last, Fidelma too steps back and bestows her smile on the gathering. ‘We will be your family for the time being. Mistress Alys, who keeps a good house for us, will show you to your rooms, then we’ll sit to an early supper. And Gwern,’ she gestures behind her without looking, ‘will bring your luggage along presently.’

A man leaves the thatched cottage and shambles towards us. Tall but crooked, his right shoulder is higher than his left and his gait is that of someone in constant pain. He is attired in the garb of gardeners and dogsbodies: tan waistcoat, breeches and leggings, a yellow shirt that may have been white, an exhausted-looking flat tweed cap, and thick-soled brown leather boots. A sheathed hunting knife hangs at his waist. His hair is black and shaggy, his eyes blacker still.

In the time it has taken us to arrive and be welcomed, the sun has slid behind the trees, and its only trace is a dying fire against the greying sky. We follow the direction of Orla’s graceful hands and tramp inside, careful to wipe our shoes on the rough stone step. The last in line, I glance back to the garden and find the gaze of the crooked man firmly on me; he is neither young nor old, nor is his a dullard’s stare, but rather calculating, considering, weighing me and judging my worth. I shiver and hope he cannot see inside me.

We troop after the housekeeper along a corridor and she points out where our classrooms are, our training areas. The rooms that are locked, she says, are locked for a reason. Then up a wide staircase, to a broad landing which splits into two thin staircases. We take the one to the right—to the left, we are told, leads to the Misses’ part of the house, and the rooms where visiting tutors will rest their heads. We traipse along more hallways than seem possible in what is a such a compact abode, past statues and paintings, vases on pedestals, flowers in said vases, shiny swords, battleaxes and shields all mounted on the wood panelled walls as if they might be ready to be pulled down and used at a moment’s notice. Yet another staircase, even narrower than the first, rickety and not a little drunk, leading to a room that should be the dusty attic, but is not. It is a large chamber, not unlike the dormitory I am used to, but much smaller, with only four beds, each with a nightstand to the left, a washstand to the right, and a clothes chest at the foot. One wall of the room is entirely made up of leadlight glass, swirling in a complex pattern of trees and limbs, wolves and wights, faeries and frights. The last of the sun-fire lights it up and we are bathed in molten colour.

‘You young ladies must be exhausted,’ fairly sings Mistress Alys in her rich contralto. ‘Choose your beds, and do not fight. Wash up and tidy yourselves, then come down for supper.’ She quietly closes the door behind her.

While my cohorts bicker over which bed covered with which patchwork quilt they shall have, I stand at the transparent wall, looking, taking in the curved backs of men hefting luggage from the top of the carriage, over the gardens, the lake and into the woods—to the place where my inner compass tells me the alder well lies.

*

The igneous colours of the afternoon have cooled and frozen in the moonlight and seem as blown glass across our coverlets. I wait until the others are breathing slowly, evenly; then I wait a little longer so that their sleep is deeper still. Exhausted though I am I will have no peace until I make my pilgrimage. Sitting up, my feet touch the rug, the thick pile soft as a kitten’s fur, and I gather my boots but do not put them on.

One last look at the sleepers around me to make sure there are no tell-tale flickers of lashes, breaths too shallow or even stopped altogether because of being held in anticipation. Nothing, although I think I detect the traces of tears still on Serafine’s face, silvery little salt crystals from where she cried prettily after being reprimanded by the Misses. At supper, I’d exclaimed with delight at one of the dishes laid before us: ‘Hen-of-the-Woods!’ and Serafine had snorted contemptuously.

‘Really, Mercia, if you plan to pass among your betters you must learn not to speak like a peasant. It’s known as Mushrooms of Autumn,’ she said, as if the meal had a pedigree and status. I looked down at my plate, hoping for the moment to simply pass quietly, but both the Meyrick sisters leapt in and explained precisely why Serafine was wrong to make fun of anyone. It was kind but almost made things worse, for it ensured the humiliation endured, stretched agonisingly, was magnified and shared. And it guaranteed that Serafine, at first merely a bully, would become an adversary for me and that might make my true task more difficult.

I tiptoe down the stairs, and slip out the kitchen door which I managed to leave unlocked after doing the evening’s dishes. Fidelma said we must all take turns assisting Mistress Alys with cleaning and cooking—this is no hardship for me, not the unaccustomed activity it is to my companions, whose privileged lives have insulated them from the rigours of housework. Orla instructed it will help us learn to fit in at every level of a household, and doing a servant’s tasks is an excellent way to slip beneath notice—which is a skill we may well be grateful for one day.

Out in the spring air I perch on the steps to pull on my boots, and sniff at the heady aroma of the herbs in the walled kitchen garden; I stand, get my bearings and set off. Do I look like a ghost in my white nightgown, flitting across the landscape? With luck no one else will be abroad at this hour. The moon is crescent, spilling just enough illumination for me to see my way clear along the drive, then to follow the line of the road and, stopping short of the town, to find the well—and the tree, its catkins hanging limp and sad.

There is a small peaked roof of age-silvered timber above a low wall of pale stone and crumbling dark mortar and, on the rim of the well, sits a silver mug attached to the spindle with a sturdy, equally silver chain. Just as they—the Postulants, Novices, Sisters and Blessed Wanderers—said it would be. I drop the cup over the edge, hear it splash, then pull its tether hand over hand until I have a part-filled goblet of liquid argent between my trembling palms.

The vessel feels terribly cold, colder than it should, and my digits tingle as I raise it. I swallow quickly, greedily, then gasp at the taste, the burn in my gullet, the numbness of my mouth as if I’d chewed monkshood leaves. The ice travels down, down, leaching into my limbs, taking my extremities for its own, locking my joints, creeping into my brain like icicles. My fingers are the claws of a raven frozen on a branch; my throat closes over like an icebound stream; my eyes are fogged as glass on a winter’s morn.

For a time I am frost-bitten, a creature of rime and hoar. Still and unbreathing.

They did not say it would be like this.

They did not say it would hurt. That it would make me panic. That I would burn with cold. That I would stay here, dead forever.

They did not say it would be like this.

Then time melts, that which felt like an aeon was but seconds. My body begins to thaw, to warm and I feel new again, freshly born, released from all my ills.

This is what they said it would be like; that, in drinking from the alder well, I would feel renewed and refreshed, that I would view the world with clear vision and an open, receptive mind. And, having drunk of the wellspring, I would be ready, ready to join them—that those who had already partaken here, the Blessed Wanderers, would recognise the flow in me.

My exhaustion is gone, washed away. I stretch upwards, bathe in the moonlight, invincible, invulnerable, eternal—until I hear the crack of a fallen twig and I fold swiftly into a crouch. Trying to make myself small I peer into the gloom, my heart beats painfully, the silver in my blood now all a’bubble, seeming to fizz and pop. Through the trees I see a shape moving calmly, unconcernedly, tall but with one shoulder risen higher than its brother, the hair a shaggy halo around a shadowed face.

Gwern.

I hold my breath. I do not think he has seen me; I do not think myself discovered. He shifts away slowly, continuing on whatever night-time errand is his and his alone. When he is out of sight, I run, as swiftly, as silently as I can, back towards St Dymphna’s. My feet seem to fly.

*

‘While the folding fan may seem the least offensive thing in the world, it has been used in at least thirteen high-profile political and forty-five marital assassinations in the past three hundred years.’ To underline her point, Orla produces a black ebony-wood fan and opens it with a sharp flick of the wrist. The item makes quite a sound as it concertinas out and she beckons us to look closer. The leaves are made of an intricately tatted lace of black and gold, the sticks are wooden, but the ribs, oh, the ribs look slightly different—they are metal, perhaps iron, and with subtly sharpened points. Orla draws our attention to the guardsticks: with a long fingernail she flicks the ends and from each pops a concealed blade. One delicate wave and a throat might be cut, one thrust and a heart pierced. I cannot help but admire the craftsmanship as we sit on the velvet-covered chaises lined against one wall of the practise room, which is located in the basement of the manor, a well-thought-out and thoroughly equipped space.

In front of us is a chalkboard covered with diagrams of innocuous-looking fans of varying designs and substances (iron, wood, reinforced linen, nacre), with the names of all their component parts for us to memorise. To our right stretches the far wall, with four practise dummies made of wood and hessian and straw, red circles painted over the heart of each one. To the left are weapons racks filled with everything one might need, including a cunningly constructed sword that breaks down to its component parts, an orb that with the touch of a button sprouts sharp spikes, and two kinds of parasols—one that has a knife in its handle, the other which converts to a tidy crossbow.

Then there are the display cases which contain all the bespoke appurtenances a lady could desire: silver-backed brushes with opiate-infused needles concealed among the bristles; hairpins and gloves and tortoise-shell hair combs equally imbued with toxins; chokers and pendants, paternosters and sashes and tippets, garters and stockings, all beautifully but solidly made and carefully reinforced so they might make admirable garrottes; boots with short stiletto blades built into both heel and toe; even porous monocles that might be steeped in sleeping solutions or acid or other corrosive liquid; hollowed-out rings and brooches for the surreptitious transport of illicit substances; decorative cuffs with under-structures of steel and whalebone to strengthen wrists required to give killing blows; fur muffs that conceal lethally weighted saps… an almost endless array of pretty deaths.

Fidelma hands us each our own practice fan—simple lightly-scented, lace-carved, sandalwood implements, lovely but not deadly, nothing sharp that might cause an accident, a torn face or a wounded classroom rival—although at the end of our stay here, we will be given the tools of our trade, for St Dymphna’s tuition fees are very grand. Orla instructs us in our paces, a series of movements to develop, firstly, our ability to use the flimsy useless things as devices for flirting: hiding mouths, highlighting eyes, misdirecting glances, keeping our complexions comfortably cool in trying circumstances.

When we have mastered that, Fidelma takes over, drilling us in the lightning fast wrist movements that will open a throat or put out an eye, even take off a finger if done with enough force, speed and the correctly-weighted fan. We learn to throw them, after first having engaged the clever little contrivances that keep the leaves open and taut. When we can send the fans spinning like dangerous discuses, then we begin working with the guardstick blades, pegging them at the dummies, some with more success than others.

There is a knock on the door, and Mistress Alys calls the Misses away. Before she goes, Orla makes us form pairs and gives each couple a bowl of sticky, soft, brightly coloured balls the size of small marbles. We are to take turns, one hurling the projectiles and the other deflecting them with her fan. As soon as the door is closed behind our instructresses, Serafine begins to chatter, launching into a discussion of wedding matters, dresses, bonbonniere, bunting, decoration, the requisite number of accompanying flower girls, honour-maids, and layers of cake. She efficiently and easily distracts Adia, who will need to learn to concentrate harder if she wishes to graduate from St Dymphna’s in time for her own wedding.

‘It seems a shame to go to all the trouble of marrying someone just to kill him,’ muses Adia. ‘All the expense and the pretty dresses and the gifts! What do you think happens to the gifts?’

‘Family honour is family honour!’ says Serafine stoutly, then ruins the effect by continuing with, ‘If you don’t do anything until a year or two after the wedding day, surely you can keep the gifts?’

The pair of them look to Veronica for confirmation, but she merely shrugs then pegs a ball of red at me. I manage to sweep it away with my fine sandalwood construct.

‘What has your fiancé done?’ asks Adia, her violet eyes wide; a blue blob adheres to her black skirt. ‘And how many flower maids will you have?’

‘Oh, his great-great-grandfather cheated mine out of a very valuable piece of land,’ says Serafine casually. ‘Five. What will you avenge?’

‘His grandfather refused my grandmother’s hand in marriage,’ Adia answers. ‘Shall you wear white? My dress is oyster and dotted with seed pearls.’

‘For shame, to dishonour a family so!’ whispers Veronica in scandalised tones. ‘My dress is eggshell, with tiers of gros point lace. My betrothed’s mother married my uncle under false pretences—pretending she was well-bred and from a prosperous family, then proceeded to bleed him dry! When she was done, he took his own life and she moved on to a new husband.’

‘Why are you marrying in now?’

‘Because now they are a prosperous family. I am to siphon as much wealth as I can back to my family before the coup de grace.’ Veronica misses the green dot I throw and it clings to her shirt. ‘What shoes will you wear?’

I cannot tell if they are more interested in marriage or murder.

‘But surely none of you wish to get caught?’ I ask, simply because I cannot help myself. ‘To die on your wedding nights? Surely you will plot and plan and strategise your actions rather than throw your lives away like …’ I do not say ‘Lady Carew’, recalling their unstinting admiration for her actions.

‘Well, it’s not ideal, no,’ says Veronica. ‘I’d rather bide my time and be cunning—frame a servant or ensure a safe escape for myself—but I will do as I’m bid by my family.’

The other two nod, giving me a look that says I cannot possibly understand family honour—from our first meeting it was established that I was not from a suitable family. They believe I am an orphan, my presence at the school sponsored by a charitable donation contributed to by all the Guilds of my city, that I might become useful tool for business interests in distant Lodellan. I’m not like them, not an assassin-bride as disposable as yesterday’s summer frock, but a serious investment. It in no way elevates me in their estimation.

They do not know I’ve never set foot in Lodellan, that I have two sisters living still, that I was raised in Cwen’s Reach in the shadow of the Citadel, yearning to be allowed to be part of its community. That I have lived these past five years as postulant then as novice, that I now stand on the brink of achieving my dearest wish—and that dearest wish has nothing to do with learning the art of murder. That Mater Friðuswith said it was worth the money to send me to St Dymphna’s to achieve her aim, but she swore I would never have to use the skills I learned at the steely hands of the Misses Meyrick. Even then, though, anxious as I was to join the secret ranks, the inner circle of the Little Sisters of St Florian, I swore to her that I would do whatever was asked of me.

As I look at these girls who are so certain they are better than me, I feel that my purpose is stronger than theirs. These girls who think death is an honour because they do not understand it—they trip gaily towards it as if it is a party they might lightly attend. I feel that death in my pursuit would surely weigh more, be more valuable than theirs—than the way their families are blithely serving their young lives up for cold revenge over ridiculous snubs that should have been long-forgotten. I shouldn’t wonder that the great families of more than one county, more than one nation, will soon die out if this tradition continues.

‘You wouldn’t understand,’ says Veronica, not unkindly, but lamely. I hide a smile and shrug.

‘My, how big your hands are, Mercia, and rough! Like a workman’s—they make your fan look quite, quite tiny!’ Serafine trills just as the door opens again and Fidelma returns. She eyes the number of coloured dots stuck to each of us; Adia loses.

‘You do realise you will repeat this activity until you get it right, Adia?’ Our teacher asks. Adia’s eyes well and she looks at the plain unvarnished planks at her feet. Serafine smirks until Fidelma adds, ‘Serafine, you will help your partner to perfect her technique. One day you may find you must rely on one of your sisters, whether born of blood or fire, to save you. You must learn the twin virtues of reliance and reliability.’

Something tells me Fidelma was not far from the classroom door while we practised. ‘Mercia and Veronica, you may proceed to the library for an hour’s reading. The door is unlocked and the books are laid out. Orla will question you about them over dinner.’

She leaves Veronica and I to pack our satchels. As I push in the exercise book filled with notes about the art of murder by fan, my quills and the tightly closed ink pot, I glance at the window.

There is Gwern, leaning on a shovel beside a half dug-over garden bed. He is not digging at this moment, though, as he stares through the pane directly at me, a grin lifting the corner of his full mouth. I feel heat coursing up my neck and sweeping across my face, rendering my skin as red as my hair. I grab up my carry-all and scurry from the room behind Veronica, while Serafine and Adia remain behind, fuming and sulking.

*

‘Nothing fancy,’ says Mistress Alys. ‘They like it plain and simple. They’ve often said “Bread’s not meant to be frivolous, and no good comes of making things appear better than they are”, which is interesting considering their business.’ She sighs fondly, shakes her head. ‘The Misses got their funny ways, like everyone else.’

I am taking up one end of the scarred oak kitchen table, elbow-deep in dough, hands (the blue tint almost gone) kneading and bullying a great ball of it, enough to make three loaves as well as dainty dinner rolls for the day’s meals. But I prick up my ears. It’s just before dawn and, although this is Adia’s month of kitchen duties, she is nursing a badly cut hand where Serafine mishandled one of the stiletto-bladed parasols during class.

The housekeeper, stand-offish and most particular at first, is one to talk of funny ways. She has gotten used to me in these past weeks and months, happy and relieved to find I am able and willing to do the dirtiest of chores and unlikely to whinge and whimper—unlike my fellow pupils. I do not complain or carp about the state of my perfectly manicured nails when doing dishes, nor protest that I will develop housewives’ knee from kneeling to scrub the floors, nor do I cough overly much when rugs need beating out in the yard. As a result, she rather likes me and has become more and more talkative, sharing the history of the house, the nearby town, and her own life. I know she lost her children, a girl and a boy, years ago when her husband, determined to cut the number of mouths to feed, led them into the deepest part of the forest and left them there as food for wolves and worms. How she, in horror, ran from him, and searched and searched and searched to no avail for her Hansie and Greta. How, heartbroken and unhinged, she finally gave up and wandered aimlessly until she found herself stumbling into Alder’s Well, and was taken in by the Misses, who by then had started their school and needed a housekeeper.

I’ve written down all she has told me in my notebook—not the one I use for class, but the one constructed of paper scraps and leaves sewn into quires then bound together, the first one I made for myself as a novice—and all the fragments recorded therein will go into a Book of Lives in the Citadel’s Archives. Not only her stories, but those of Adia, Serafine and Veronica, and the tiny hints Alys drops about Orla and Fidelma, all the little remnants that might be of use to someone some day; all the tiny recordings that would otherwise be lost. I blank my mind the way Mater Friðuswith taught me, creating a tabula rasa, to catch the tales there in the spider webs of my memory.

‘Mind you, I suppose they’ve got more reason than most.’

‘How so?’ I ask, making my tone soothing, trustworthy, careful not to startle her into thinking better of saying anything more. She smiles gently down at the chickens she is plucking and dressing, not really looking at me.

‘Poor pets,’ she croons, ‘Dragged from battlefield to battlefield by their father—a general he was, a great murderer of men, their mother dead years before, and these little mites learning nothing but sadness and slaughter. When he finally died, they were released, and set up here to help young women such as you, Mercia.’

I cover my disappointment—I know, perhaps, more than she. This history is a little too pat, a tad too kind—rather different to the one I read in the Archives in preparation for coming here. Alys may well know that account, too, and choose to tell me the gentler version—Mater Friðuswith has often said that we make our tales as we must, constructing stories to hold us together.

I know that their mother was the daughter of a rich and powerful lord—not quite a king, but almost—a woman happy enough to welcome her father’s all-conquering general between her thighs only until the consequences became apparent. She strapped and swaddled herself so the growing bump would not be recognised, sequestered herself away pleading a dose of some plague or other—unpleasant but not lethal—until she had spat forth her offspring and they could be smuggled out and handed to their father in the depths of night, all so their grandfather might not get wind that his beloved daughter had been so stained. This subterfuge might well have worked, too, had it not been for an unfortunate incident at a dinner party to welcome the young woman’s paternally-approved betrothed, when a low-necked gown was unable to contain her milk-filled breasts, and the lovely and pure Ophelia was discovered to be lactating like a common wet nurse.

Before her forced retirement to a convent where she was to pass her remaining days alternatively praying to whomever might be listening, and cursing the unfortunate turn her life had taken, she revealed the name of the man who’d beaten her betrothed to the tupping post. Her father, his many months of delicate planning, negotiating, strategising and jostling for advantage in the sale of his one and only child, was not best pleased. Unable to unseat the General due his great popularity with both the army and the people, the Lord did his best to have him discreetly killed, on and off the battlefield, sending wave after wave of unsuccessful assassins.

In the end, though, fate took a hand and the Lord’s wishes were at last fulfilled by an opportune dose of dysentery, which finished off the General and left the by-then teenage twins, Fidelma and Orla, without a protector. They fled, taking what loot they could from the war chests, crossing oceans and continents and washing up where they might. Alas, their refuges were invariably winkled out by their grandfather’s spies and myriad attempts made on their lives in the hope of wiping away all trace of the shame left by their mother’s misdeeds.

The records are uncertain as to what happened, precisely—and it is to be hoped that the blanks might be filled in one day—but in the end, their grandfather met a gruesome death at the hands of an unknown assassin or assassins. The young women, freed of the spectre of an avenging forebear, settled in Alder’s Well, and set up their school, teaching the thing they knew so well, the only lesson life had ever taught them truly: delivering death.

‘Every successful army has its assassins, its snipers, its wetdeedsmen—its Quiet Men,’ Orla had said in our first class—on the art of garrotting, ‘And when an entire army is simply too big and too unwieldy for a particular task one requires the Quiet Men—or in our case, Quiet Women—to ensure those duties are executed.’

‘One doesn’t seek an axe to remove a splinter from a finger, after all,’ said Fidelma as she began demonstrating how one could use whatever might be at hand to choke the life from some poor unfortunate: scarf, silk stockings, stays, shoe or hair ribbons, curtain ties, sashes both military and decorative, rosaries, strings of pearls or very sturdy chains. We were discouraged from using wire of any sort, for it made a great mess, and one might find one’s chances of escape hindered if found with scads of ichor down the front of a ball or wedding gown. Adia, Seraphine and Veronica had nodded most seriously at that piece of advice.

Mistress Alys knew what her Misses did, as well as did white-haired Mater Friðuswith when she’d sent me here. But perhaps it was easier for the dear housekeeper to think otherwise. She’d adopted them and they her. There was a kind of love between them, the childless woman and the motherless girls.

I did not judge her for we all tell ourselves lies in order to live.

‘There he is!’ She flies to the kitchen window and taps at the glass so loudly I fear the pane will fall out of its leadlight bedding. Gwern, who is passing by, turns his head and gazes sourly at her. She gestures for him to come in and says loudly, ‘It’s time.’

His shoulders slump but he nods.

‘Every month,’ she mutters as if displeased with a recalcitrant dog. ‘He knows every month it’s time but still I have to chase him.’

She pulls a large, tea-brown case with brass fittings from the top of a cupboard and places it at the opposite end of the table to me. Once she’s opened it, I can see sharp, thick-looking needles with wide circular bases; several lengths of flexible tubing made perhaps of animal skin or bladder, with what seem to be weighted washers at each end; strange glass, brass and silver objects with a bell-shaped container at one end and a handle with twin circles at the other, rather like the eye rings of sewing scissors. Alys pulls and pushes, sliding them back and forth—air whooshes in and out. She takes the end of one length of tubing and screws it over a hole in the side of the glass chamber, and to the other end she affixes one of the large gauge needles. She hesitates, looks at me long and hard, pursing her lips, then I see the spark in her eyes as she makes a decision. ‘Mercia, you may stay, but don’t tell the Misses.’

I nod, but ask, ‘Are you sure?’

‘I need more help around here than I’ve got and you’re quiet and accommodating. I’ll have your aid while I can.’

By the time she returns to the cupboard and brings out two dozen tiny crystal bottles, Gwern has stepped into the kitchen. He sits and rolls up his sleeves, high so that the soft white flesh in the crooks of his elbows is exposed. He watches Alys with the same expression as a resentful hound, wanting to bite but refraining in the knowledge of past experience.

Mistress Alys pulls on a pair of brown kid gloves, loops a leather thong around his upper arm, then pokes at the pale skin until a blue-green relief map stands out. She takes the needle and pushes it gently, motherly, into the erect vein. When it’s embedded, she makes sure the bottom of the bell is safely set on the tabletop, and pulls on the pump, up and up and up, slowly as if fighting a battle—sweat beads her forehead. I watch as something dark and slow creeps along the translucent tubing, then spits out into the bottom of the container: green thick blood. Liquid that moves sluggishly of its own accord as the quantity increases. When the vessel is full, Alys begins the process again with the other arm and a new jar which she deftly screws onto the base of the handle.

She pushes the full one at me, nodding towards a second pair of kid gloves in the case. ‘Into each of those—use the funnel,’ she nods her head at the vials with their little silver screw tops, ‘Don’t over-fill and be careful not to get any on yourself—it’s the deadliest thing in the world.’ She says this last with something approaching glee and I risk a glance at Gwern. He is barely conscious now, almost reclining, limbs loose, head lolling over the back of the chair, eyes closed.

‘Is he alright?’ I ask, alarmed. I know that when I lay down to sleep this eve, all I shall see is this man, his vulnerability as something precious is stolen from him. Somehow, witnessing this has lodged the thought of him inside me.

She smiles, pats his cheek gently and nods. ‘He’ll be no good to anyone for the rest of the day; we’ll let him sleep it off—there’s a pallet bed folded in the pantry. You can set that up by the stove when you’ve done with those bottles. Shut them tightly, shine them up nice, the Misses have buyers already. Not that there’s ever a month when we have leftovers.’

‘Who—what—is he?’ I ask.

She runs a tender hand through his hair. ‘Something the Misses found and kept. Something from beneath or above or in-between. Something strange and dangerous and he’s ours. His blood’s kept our heads above water more than once—folk don’t always want their daughters trained to kill, but there’s always call for this.’

I wonder how they trapped him, how they keep him here. I wonder who he was—is. I wonder what he would do if given his freedom. I wonder what he would visit upon those who’ve taken so much from him.

‘Hurry up, Mercia. Still plenty to do and he’ll be a handful to get on that cot. Move yourself along, girl.’

*

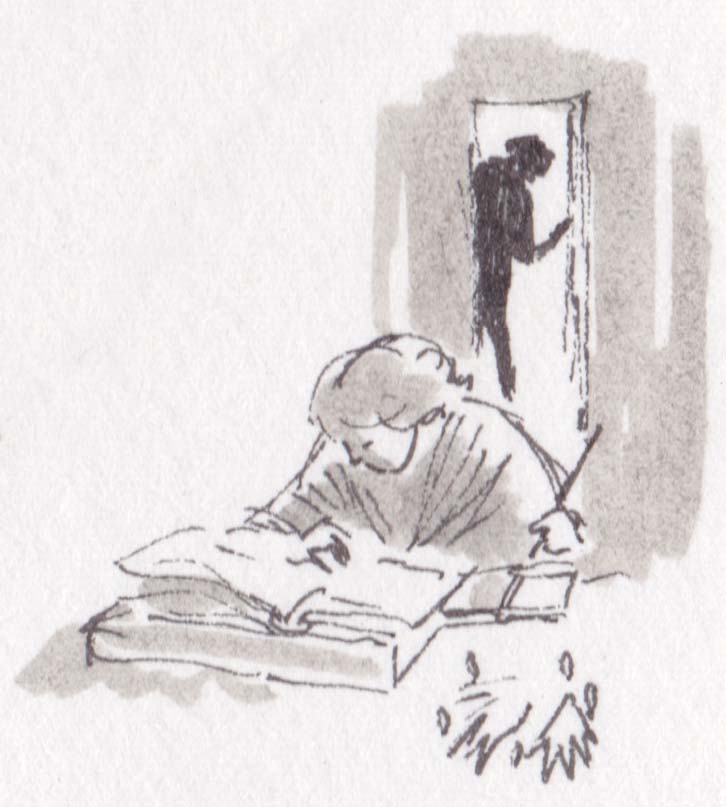

When I hear a board creak, I glance at the two hands of glory, and notice that of the seven fingers I lit, only six still burn and my heart ices up.

I have been careful, so careful these past months to quietly pick the lock on the library door, then close it after me, pull the curtains over so no light might be seen in the windows, before I kindle one finger-candle for each inhabitant of the house, then lay out my quills and books, the pounce pot, and open the special volume Mater Friðuswith gave me for this specific duty. Generations of St Florian’s abbesses have asked many, many times for permission to copy The Compendium of Contaminants—rumoured to be the work of the first of us—yet time and again the Misses have refused access.

They guard their secrets jealously and this book is alone of all its kind. Their ownership of the only extant copy is an advantage they will not surrender, even though the Murcianii, the Blessed Wanderers, seek only to record and keep the information. There are to be found fragments of this greatest of poisoners’ bibles, yes; copies with pages missing, edges burned, ink run or faded—but none virgo intacto like this one. None so perfect, so filled with recipes and instructions, magical and medicinal properties and warnings, maps of every manner of plant and where it might be found, how it might best be harvested and then propagated elsewhere, how it might best be used for good or ill, how it might be preserved or destroyed. Without it our Archives are embarrassingly bereft, and with only one single copy in existence, the possibility of its destruction is too great for us to bear.

And this is why I am here; this is my initiation task to earn my place among St Florian’s secret sisters, the Murcianii, the collectors, the recorders, the travelling scribes who gather all manner of esoteric and eldritch knowledge so it might not pass out of the world. Folktales and legends, magic and spells, bestiaries of creatures once here and now long-gone, histories and snippets of lives that have intersected with our efforts, our recordings… and books like these, the dark books, the dangerous books, the books that some would burn but which we save because knowledge, all knowledge, is too important to be lost.

If I bring a copy of this book back to Mater Friðuswith then my position will be assured. I will belong.

But all that will be moot if I am discovered; if my betrayal of two of the most dangerous women of the day—indeed other days, long ago—is found out.

The door opens and Gwern stands there, clothes crumpled from his long sleep, hair askew, the marks of a folded blanket obvious along his jaw line. He sways, still weak from the bloodletting, but his eyes are bright.

‘What are you doing?’ The low voice runs through me. Part of me notes that he seems careful to whisper. He takes in the Compendium, propped on the bookstand, all the tools of my trade neatly lined up on the desk (as untidy as my person may be, I am a conscientious craftswoman), and the hands of glory by whose merrily flickering light I have been working.

And I cannot answer; fear stops my throat and all I can think of is Fidelma and Orla and their lethal ornaments, the choking length of a rosary about my neck, a meal infused with tincture of Gwern’s lifeblood, a down-stuffed pillow over my face as I sleep. He steps into the room, closes the door behind him then paces over to lift me up by the scruff of the neck as if I am a kitten who’s peed in his shoes. Not so weak as he seems, then. He shakes me til I think my head will roll off, until he realises I cannot explain myself if I cannot breathe. He lets me go, pushing me back until I sit on top of the desk and draw in great gasps of air, and he asks me again in that threatening tone, ‘What are you doing?’

And I, in fear of what might happen if two Quiet Women should find out what I’ve been doing, how I’ve been taking from them what they’ve refused—and hoping, perhaps, after what I’d witnessed this morning that he might not have much love for the Misses—I tell him almost everything.

And when I am finished, he does not call out and rouse the Meyrick sisters. He does not bend forward and blow out the gory candles, but rather smiles. He leans so close that I can smell his breath, earthy as freshly mown grass, as he speaks, ‘I knew it. I knew when I saw you that night.’

‘Knew what?’ I demand, momentarily brave.

‘That you were different to them; different to the others who have come here year upon tiresome year. When I saw you in the moonlight, I knew—none of the others ever venture out past the walls at night, certainly don’t wander to the well and drink its contents down so sure and so fast. They don’t make brave girls here—they make cowardly little bits who like blades in the dark, poison in the soup, pillows over faces.’ He straightens, rolls his uneven shoulders. ‘I knew you could help me.’

‘Help you do what?’ I ask, mesmerised by his black gaze.

Instead of answering, he goes to one of the shelves and rummages, finds a slim yellow volume and hands it to me. A Brief History of the Alder Well. He says nothing more, but runs a hand down the side of my face, then leaves, the door closing with a gentle click behind him. I feel his fingers on me long after he’s gone.

*

The alchemy laboratory is situated on the ground floor; it has large windows to let in light and equally large shutters to keep out the selfsame when we work with compounds that prefer the darkness. We each have a workbench, honeycombed with drawers filled with plants, powders, poisons, equipment, mortars, pestles, vials, and the like. On mine this morning, I found a rose, red as blood, its stem neatly sheared on an angle, the thorns thoughtfully removed; my heart beats faster to see it, that kindness. Indeed there’s been a floral offering every day for the past three weeks, roses, peonies, lily of the valley, snowdrops, bluebells, daffodils, all waiting for me in various spots: windowsills, shelves, under my pillow, on the kitchen bench, in the top drawer of my bedside table, hidden among the clothes in my chest. As if I needed anything to keep their giver in my thoughts; as if my dreams have not been haunted. Nothing huge, nothing spectacular, no grand bouquets, but something sweet and singular and strange; something to catch my eye alone—no one else seems to notice them. Not even Serafine with her cruel hawk’s gaze.

We have a new teacher for this sennight, who arrived with many boxes and trunks, cases and carpet bags, and a rectangular item neatly wrapped around with black velvet. When her driver seemed careless with it, she became sharp with him. It must be delicate, perhaps made of glass—mirror? A painting? A portrait?

The poisoner is fascinated by Serafine. In fact, we others may as well not be here. She hovers over the sleek blonde girl’s work-table, helping her to measure powders, cut toxic plants, heat solutions, giving her hints that we may or may not hear and take advantage of. My copying of the Compendium means my cognizance of poisons and their uses is greater than my companions but I cannot show off; cannot appear to have knowledge I should not possess.

We are not working with killing venin today, merely things to cause discomfort—a powder sprinkled over clothing or a few drops of liquid added to someone’s jar of night cream will bring up a rash, afflict the victim with itches and aches that appear to have no logical source. One must be careful, Hepsibah Ballantyne tells us in a rare address to the whole class, not to do things that disrupt a person’s ordinary routine—that is what they will remember, the disruptions: the tinker come to a door selling perfumes, the offer of a special new blend of tea from a recent acquaintance. When you wish to injure someone, do something that rubs along with their habits, their everyday lives—blend into the ordinary flow and simply corrupt one of their accustomed patterns. No fanfare, no drawing of attention to yourself or your acts. Do nothing that someone might later recall as out of the ordinary—it will bring the authorities to you faster than you please.

Mistress Ballantyne arrives once a year to stay with the Misses and impart her venomous wisdom, although Alys tells me this is not her profession proper. She is a coffin-maker and most successful—she travelled here in her own carriage and four (the driver currently making himself at home in Alys’s bed). Years and experience have made her a talented poisoner, although few know it and that’s as it should be. I think she is older than she seems, rather like the Misses; in certain lights her face is as lined as a piece of badly prepared parchment, in others it seems smooth. She has short blonde curls, and brown eyes that watched peachy-pink Serafine too closely from the moment she was introduced.

I take the apple seeds and crush them under the blade of my knife.

‘How did you know to do that?’ Hepsibah’s voice is at my shoulder and I suppress the urge to jump guiltily. The recipe in front of us says to grind the seeds in the mortar and pestle, but the Compendium warns against that as weakening the poison—crush the seeds just once with a sharp hit to crack the carapace and release the toxin. I look into her dark eyes and the lie comes quickly to my lips.

‘My mother. She learned herbcraft to support us after my father died.’ Which is true to some extent: Wulfwyn did learn herblore at St Florian’s after Mater Friðuswith offered her refuge, but our father had been well and truly gone for many years before that—or rather, my sisters’ father. Mine hung around on moonlit nights, watching from the shadows as I grew. ‘She wasn’t a poison-woman, but she knew some things, just enough to help get by.’

Her gaze softens. I’ve touched a nerve; she’s another motherless girl, I suspect. We are legion. She nods and moves away, telling me my labours are good and I show promise. Hepsibah gives Adia and Veronica’s work a quick once-over and shifts her attention back to Serafine, resting a calloused and stained hand in the small of the other’s back. I notice Serafine leans into the touch rather than away, and feel an unaccustomed wave of sympathy for her, to know she longs for something she will not be allowed to have.

*

Standing outside the library door, one hand balancing a platter of sweetmeats, the other preparing to knock and offer the Misses and their guest an evening treat to go with the decanter of winterplum brandy I delivered earlier along with three fine crystal snifters. A terse voice from inside the room stops me. I slow my breathing to almost nothing, stand utterly still; if I’ve learned nothing else here it’s to be undetectable when required.

‘Sweet Jesu, Hepsibah, control yourself!’ Orla’s voice, strangely harsh and raised in an anger none of us have yet witnessed in the classroom no matter how egregious our trespasses.

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ Mistress Ballantyne answers, her tone airy.

‘I saw you in the garden this afternoon, busy fingers, busy lips, busy teeth,’ hisses Orla.

‘Jealous?’ laughs Hepsibah.

Fidelma breaks in, ‘We have told you that you cannot touch any student in our care.’

‘That one was thoroughly touched and not complaining, besides,’ retorts Hepsibah and I imagine a wolfish grin crossing her lips.

‘Scandals! They follow you! It’s your own fault—one then another, ruined girls, angry families and you must leave a city yet again.’ Orla pauses, and I hear the sound of a decanter hitting the rim of a glass a little too hard. ‘Lord, just find someone who wants your attention, who isn’t already spoken for, and be content.’

Mistress Ballantyne snorts and I imagine she shrugs, raising her thin shoulders, tossing her neat, compact head with its pixie features and upturned nose. She might fidget, too, with those stained fingers and her small square hands; she asks belligerently, ‘Where’s the fun in a willing victim?’

Fidelma fairly shouts, ‘He has been seen. Not two counties away.’

And silence falls as if a sudden winter has breathed over the library and frozen its inhabitants. It lasts until Mistress Ballantyne breaks it, all swagger, all arrogance gone, her voice rises to a shriek, ‘Has he been here? Have you betrayed me?’

Fidelma shushes her. ‘Of course not, you silly bint, but people talk, rumours have wings. Those who live long and do not change as much as others become the target of gossip. Those who do not hide, who do not take care not to draw attention—they are the ones who stand out, Hepsibah.’

Orla sighs. ‘And you know he’s been searching for something, something other than you—in addition to you. We do not live in a large city, Hepsibah, we do not live in a grand house and parade along boulevards in an open-topped landau, begging folk to stare and take note. Few people know who we truly are, fewer still that the wars our father fought ended a hundred years ago.’

Fidelma: ‘It’s a wonder you survived in the days before you knew he was hunting you. You’ve never learned the art of hiding yourself—of putting your safety ahead of your baser desires.’

‘You’ve had good service of me. I’ve shared my secrets with you, helped keep you young, taught your murderous little slatterns who think they’re better than me.’ There’s a pause, perhaps she worries at a thumbnail. ‘But if he’s been seen, then I’m off.’

‘But you’ve still got classes to teach!’ protests Orla.

Hepsibah shrugged. ‘Well, consider that I’m thinking of my own safety before my baser desires,’ she sneers. ‘Get Magnus, she’s a good poisons woman if you can find her. Last I heard she’d berthed in Breakwater.’

There are quick footsteps and the door is wrenched open. I’m almost bowled over by Mistress Ballantyne, who shouts ‘Out of my way, halfwit’ and charges off towards her room. The Misses stare at me and I hold up the tray of sweetmeats, miraculously not thrown to the floor as Hepsibah passed. Orla gestured for me to come in, then turns to her sister. ‘You see if you can talk sense to her. I’m not teaching poisons.’

‘You’re the one who mentioned him. If it comes down to it, sister, you will.’

Fidelma sweeps out, taking a handful of sweetmeats with her. Orla slumps in a chair and, when I ask if there’s anything else she needs, she waves me away, not bothering to answer. On the small table beside her are three discarded vials, red-brown stains in the bottom.

I will not make my nest in the library tonight. Mistress Ballantyne will take a while to pack her trunks and rouse her coachman from the warmth of Alys’s blankets. The household will be in uproar this night and I shall take the chance to have a sleep uninterrupted by late-night forgery at least; there will be no guarantee that I will not dream of Gwern. One night without copying the Compendium will not make much difference.

*

Orla’s grace has deserted her.

All the patience and fine humour she’s displayed in the past is gone, replaced by an uncertain and somewhat foul temper, as if she’s been tainted by the subject she’s forced to teach. The Misses, wedded to their schedule, decided not to try for the woman Magnus, and it is as Fidelma threatened: Orla, having caused the difficulty, must now deal with the consequences.

Open on the desk in front of her is the Compendium as if it might solve all of her problems. I wonder if Mistress Alys with her fondness for herbs wouldn’t have been a better choice. I keep looking at the book, suppressing shudders each time Orla’s hands—filled with a toxic powder, wilted stalk or simple spring water—pass anywhere near it. It is unique, alone in the world and I feel it must be protected. Coiled, I wait to leap forward and save it from whatever careless fate Orla might bestow upon it.

The ingenuity and patience, which is so fully in evidence when teaching us how to kill using unthought-of weapons, has left no trace as Orla makes us mix concoctions, elixirs and philtres to cause subtle death. She forgets ingredients, tells us to stir when we should shake, to grind when we should slice, to chop when we should grate. We are not halfway through the first lesson when our tutor swears loudly and knocks over a potion, which pours into an alabaster mortar and mates with the crushed roots there. The reaction is spectacular, a fizz and a crack and smoke of green then purple fills the alchemy room like a sudden, vitriolic fog.

I throw open the windows, shielding my mouth and nose with the bottom of my skirt, then I find the door and thrust it to—the smoke begins to clear but all I can hear are the rasping coughs of my fellow students and teacher. Squinting against the tears the smoke causes, I find them one by one and herd them out into the corridor, where Mistress Alys and Fidelma, drawn by the noise, are in a flurry. When Orla is the last one out, I dive back into the room and rescue the book—it tore at me not to save it before any mortal, but common sense prevailed and no suspicions are aroused. I hold it tightly to my chest as we are all hustled outside into the fresh air.

‘Well done, Mercia,’ says Fidelma, bending down to pat her sister’s heaving back. Orla vomits on the grass, just a little.

‘There’s no fire, Miss, just the smoke. It should clear out soon—there’s a good enough breeze,’ I say.

‘Indeed.’ She stands and surveys the lilac-tinged vapour gently wafting through the door behind us. ‘We are nothing if not adaptable. I think we shall leave the rest of our poisons classes until such time as Mother Magnus or a suitable substitute might be found—lest my sister kill us all.’

Orla makes an unladylike gesture and continues coughing. Mistress Alys, having braved the smog, reappears with a syrupy cordial of black horehound, to soothe our throats and lungs. We swig from the bottle.

Some time later, order has been restored: the house has been cleared of the foul smelling fumes; pleural barks have been reduced to occasional rattles; Orla’s dignity has been stitched together for the most part; and I have (with concealed reluctance) handed back the Compendium and been given by Fidelma a letter for Mother Magnus and instructed to deliver it to the coachman who resides in Alder’s Well, begging him to deliver it to the poisons woman and wait for her reply—and hopefully her agreement to return with him.

I walk slowly there and even more slowly back, enjoying the air, the quiet that is not interrupted by the prattle of girls too silly to know they will be going to their deaths sooner than they should—too silly to know that now is the time they should begin mourning their lost futures. Or planning to run away, to fade from their lives. Gods know we are taught enough means to hide, to provide for ourselves, to change our appearances, to earn a living in different ways, to disappear. Sometimes I am tempted to tell Veronica about Cwen’s Reach and the Citadel, about the Little Sisters of St Florian and how they offered my family refuge, and how, for a long time, no one found us, not even Cenred’s ghost. How she could just as easily come with me and become one of the sisters or live in the city at the Citadel’s foot as Delling and Halle do, working as jewel-smiths. But I know better. I know she would not want to lose her soft life even for the advantage of longevity; she will play princess while she may, then give it all up not for a lesser lifestyle, but for death. Because she thinks with death, everything stops.

I could tell her otherwise. I could tell her how my mother was pursued by her brother’s shade for long years. How he managed somehow to still touch her, to get inside her, to father me well after he was nothing more than a weaving of spite and moonlight. How I would wake from a dream of him whispering that my mother would never escape him. How, even at her death bed, he hovered. How, until Delling did her great and pious labour, he troubled my sleep and threatened to own me as he had Wulfwyn. I could tell her that dying is not the end—but she will discover it herself soon enough.

I had not thought to go back by the clearing, but find myself there anyway, standing before both well and alder. They look different to that first night, less potent without their cloak of midnight light. Less powerful, more ordinary. But I do not forget the burning of the well’s water; nor my first sight of the alder and the man who seemed crucified against it, wormed through with vines and mistletoe.

‘Have you read it? The little book?’

I did not hear him until he spoke, standing beside me. For a large, limping man he moves more silently than any mortal should. Then again, he is not mortal, but I am unsure if he is what he would have me believe. Yet I have seen his blood. I give credence to things others would not countenance: that my father was a ghost and haunted my dreams; that the very first of the scribes, Murciana, could make what she’d heard appear on her very skin; that the Misses are older than Mater Friðuswith although they look young enough to be her daughters—granddaughters in some lights. So, why not believe him?

I nod, and ask what I’ve been too shy to ask before, ‘How did you come here?’

He taps the trunk of the alder, not casually, not gently, but as if in hope that it will become something more. It disappoints him, I can see. His hand relaxes the way one’s shoulders might in despair.

‘Once upon a time I travelled through these. They lead down, you see, into under-earth. Down to the place I belong. I was looking for my daughter—a whisper said she was here, learning the lessons these ones might teach.’

And I think of the little yellow book, written by some long-dead parson who doubled as the town’s historian. The Erl-King who rules beneath has been sighted in Alder’s Well for many a year. Inhabitants of the town claim to have seen him roaming the woods on moonlit nights, as if seeking someone. Parents are careful to hide their children, and the Erl-King is often used to frighten naughty offspring into doing what they’re bid. My own grand-dam used to threaten us with the words ‘Eat your greens or the Erl-King will find you. And if not him then his daughter who wanders the earth looking for children to pay her fare back home.’ Legend has it he travels by shadow tree.

‘Did you find her? Where is she?’

He nods. ‘She was here then, when I came through. Now, I no longer know. She had—caused me offence long ago, and I’d punished her. But I was tired of my anger and I missed her—and she’d sent me much… tribute. But I did not think that perhaps her anger burned brightly still.’

No one is what they seem at St Dymphna’s. ‘Can’t you leave by this same means?’

He shakes his great head, squeezes his eyes closed. It costs his pride much to tell me this. ‘They tricked me, trapped me. Your Misses pinned me to one of my own shadow trees with mistletoe, pierced me through so my blood ran, then they bound me up with golden bough—my own trees don’t recognise me anymore because I’m corrupted, won’t let me through. My kingdom is closed to me, has been for nigh on fifty years.’

I say nothing. A memory pricks at me; something I’ve read in the Archives… a tale recorded by a Sister Rikke, of the Plague Maiden, Ella, who appeared from an icy lake, then disappeared with all the village children in tow. I wonder… I wonder…

‘They keep me here, bleed me dry for their poison parlour, sell my blood as if it’s some commodity. As if they have a right.’ Rage wells up. ‘Murderous whores they are and would keep a king bound!!’

I know what—who—he thinks he is and yet he has provided no proof, merely given me this book he may well have read himself and taken the myths and legends of the Erl-King and his shadow trees to heart. Perhaps he is a madman and that is all.

As if he divines my thoughts, he looks at me sharply.

‘I may not be all that I was, but there are still creatures that obey my will,’ he says and crouches down, digs his fingers firmly into the earth and begins to hum. Should I take this moment to run? He will know where to find me. He need only bide his time—if I complain to the Misses, he will tell what he knows of me.

So I wait, and in waiting, I am rewarded.

From the forest around us, from behind trees and padding from the undergrowth they come; some russet and sleek, some plump and auburn, some young, some with the silver of age dimming their fur. Their snouts pointed, teeth sharp, ears twitching alert and tails so thick and bushy that my fellow students would kill for a stole made from them. They come, the foxes, creeping towards us like a waiting tribe. The come to him, to Gwern, and rub themselves against his legs, beg for pats from his large calloused hands.

‘Come,’ he says to me, ‘they’ll not hurt you. Feel how soft their fur is.’

Their scent is strong, but they let me pet them, yipping contentedly as if they are dogs—and they are, his dogs. I think of the vision of the crucified man I saw on my first day here, of the halo of ebony hair, of the eyes briefly open and so black in the face so pale. Gwern draws me close, undoes the thick plait of my hair and runs his hands through it. I do not protest.

I am so close to giving up everything I am when I hear voices. Gwern lets me go and I look towards the noise, see Serafine, Adia and Veronica appear, each one trailing a basket part-filled with blackberries, then turn back to find Gwern is gone. The foxes melt quickly away, but I see from the shifting of Serafine’s expression that she saw something.

‘You should brush your hair, Mercia,’ she calls slyly. ‘Oh, I see you already have.’

I walk past them, head down, my heart trying to kick its way out of my chest.

‘I suppose you should have a husband,’ says Serafine in a low voice, ‘but don’t you think the gardener is beneath even you?’

‘I’d thought, Serafine, you’d lost your interest in husbands after Mistress Ballantyne’s instructive though brief visit,’ I retort and can feel the heat of her glare on the back of my neck until I am well away from them.

*

Alys is rolling out pastry for shells and I am adding sugar to the boiling mass of blackberries the others picked, when Fidelma calls from the doorway, ‘Mercia. Follow me.’

She leads me to the library, where Orla waits. They take up the chairs they occupied on the night when their nuncheon with Mistress Ballantyne went so very wrong. Orla gestures for me to take the third armchair—all three have been pushed close together to form an intimate triangle. I do so and watch their hands for a moment: Orla’s curl in her lap, tighter than a new rose; Fidelma’s rest on the armrests, she’s trying hard not to press her fingertips hard into the fabric, but I can see the little dents they make on the padding.

‘It has come to our attention, Mercia,’ begins Fidelma, who stops, purses her lips, begins again. ‘It has come to our attention that you have, perhaps, become embroiled in something… unsavoury.’

And that, that word, makes me laugh with surprise—not simply because it’s ridiculous but because it’s ridiculous from the mouths of these two! The laugh—that’s what saves me. The guilty do not laugh in such a way; the guilty defend themselves roundly, piously, spiritedly.

‘Would you listen to Serafine?’ I ask mildly. ‘You know how she dislikes me.’

The sisters exchange a look then Fidelma lets out a breath and seems to deflate. Orla leans forward and her face is so close to mine that I can smell the odour of her thick make-up, and see the tiny cracks where crows’ feet try to make their imprint at the corners of her particoloured eyes.

‘We know you speak with him, Mercia, we have seen you, but if you swear there is nothing untoward going on we will believe you,’ she says and I doubt it. ‘But be wary.’

‘He has become a friend, it is true,’ I admit, knowing that lies kept closest to the truth have the greatest power. ‘I have found it useful to discuss plants and herbs with him as extra study for poisons class—I speak to Mistress Alys in this wise too, so I will not be lacking if—when—Mother Magnus arrives.’ I drop my voice, as if giving them a secret. ‘And it is often easier to speak with Gwern than with the other students. He does not treat me as though I am less than he is.’

‘Oh, child. Gwern is… in our custody. He mistreated his daughter and as punishment he is indentured to us,’ lies Orla. To tell me this… they cannot know that I know about Gwern’s blood. They cannot know what Mistress Alys has let slip.

‘He’s dangerous, Mercia. His Ella fled and came to us seeking justice,’ says Fidelma urgently. Her fingers drummed on the taut armchair material. Whatever untruths they tell me, I think that this Ella appealed to them because they looked at her and saw themselves so many years before. A girl lost and wandering, misused by her family and the world. Not that they will admit it to me, but the fact she offered them a lifeline—her father’s unique blood—merely sweetened the deal. And, I suspect, this Ella found in the Misses the opportunity for a revenge that had been simmering for many a long year.

‘Promise us you will not have any more to do with him than you must?’ begs Orla and I smile.

‘I understand,’ I say and nod, leaning forward and taking a hand from each and pressing it warmly with my own. I look them straight in the eyes and repeat, ‘I understand. I will be careful with the brute.’

‘Love is a distraction, Mercia; it will divert you from the path of what you truly want. You have a great future—your Guilds will be most pleased when you return to them for they will find you a most-able assassin. And when your indenture to them is done, as one day it shall be, you will find yourself a sought-after freelancer, lovely girl. We will pass work your way if you wish—and we would be honoured if you would join us on occasion, like Mistress Ballantyne does—did.’

The Misses seem overwhelmed with relief and overly generous as a result; the atmosphere has been leeched of its tension and mistrust. They believe me to be ever the compliant, quiet girl.

They cannot know how different I am—not merely from their idea of me, but how different I am to myself. The girl who arrived here, who stole through the night to drink from the alder well, who regularly picked the lock on the library and copied the contents of their most precious possession, the girl who wished most dearly for nothing else in the world but to join the secret sisters. To become one of the wandering scribes who collected strange knowledge, who kept it safe, preserved it, made sure it remained in the world, was not lost nor hidden away. That girl… that girl has not roused herself from bed these past evenings to copy the Compendium. She has not felt the pull and burn of duty, the sharp desire to do what she was sent here to do. That girl has surrendered herself to dreams of a man she at first thought… strange… a man who now occupies her waking and slumbering thoughts.

I wonder that the fire that once burned within me has cooled and I wonder if I am such a fickle creature that I will throw aside a lifetime of devotion for the touch of a man. I know only that the Compendium, that Mater Friðuswith’s approval, that a place among the dusty-heeled wandering scribes are no longer pushing me along the path I was certain I wished to take.

*

‘Here, you do it!’ says Mistress Alys, all exasperation; she’s not annoyed with me, though. Gwern has been dodging her for the past few days. Small wonder: it’s bleeding time again. She pushes the brown case at me and I can hear the glass and metal things inside rattling in protest. ‘Don’t worry about the little bottles, just bring me back one full bell. I’m going in Alder’s Well and I’ll take the Misses Three with me.’

‘But …’ I say, perplexed as to how I might refuse this task of harvesting. She mistakes my hesitation for fright.

‘He’s taken a liking to you, Mercia, don’t you worry. He’ll behave well enough once he sees you. He’s just like a bloody hound, hiding when he’s in trouble.’ Alys pushes me towards the door, making encouraging noises and pouring forth helpful homilies.

Gwern’s cottage is dark and dim inside. Neither foul nor dirty, but mostly unlit to remind him of home, a comfort and an ache at the same time, I think. It is a large open space, with a double bed in one corner covered by a thick eiderdown, a tiny kitchen in another, a wash stand in another and an old, deep armchair and small table in the last. There is neither carpet nor rug, but moss with a thick, springy pile. Plants grow along the skirting boards, and vines climb the walls. Night-flowering blooms, with no daylight to send their senses back to sleep, stay open all the time, bringing colour and a dimly glimmering illumination to the abode.

Gwern sits, unmoving, in the armchair. His eyes rove over me and the case I carry. He shakes his head.

‘I cannot do it anymore.’ He runs shaking hands through his hair, then leans his face into them, speaking to the ground. ‘Every time, I am weaker. Every time it takes me longer to recover. You must help me, Mercia.’

‘What can I do?’

He stands suddenly and pulls his shirt over his head. He turns his back to me and points at the base of his neck, where there is a lump bigger than a vertebrae. I put down the case and step over to him. I run my fingers over the knots, then down his spine, finding more bumps than should be there; my hand trembles to touch him so. I squint in the dim light and examine the line of bone more carefully, fingertips delicately moulding and shaping what lies there, unrelenting and stubbornly… fibrous.

‘It’s mistletoe,’ Gwern says, his voice vibrating. ‘It binds me here. I can’t remove it myself, can’t leave the grounds of the school to seek out a physick, have never trusted any of the little chits who come here to learn the art of slaughter. And dearly though I would love to have killed the Misses, I would still not be free for this thing in me binds me to Alder’s Well.’ He laughs. ‘Until you, little sneak-thief. Take my knife and cut this out of me.’

‘How I can I do that? What if I cripple you?’ I know enough to know that cutting into the body, the spine, with no idea of what to do is not a good thing—that there will be no miraculous regeneration, for mortal magic has its limits.

‘Do not fear. Once it’s gone, what I am will reassert itself. I will heal quickly, little one, in my true shape.’ He turns and smiles; kisses me and when he draws away I find he has pressed his hunting knife into my hand.

‘I will need more light,’ I say, my voice quivering.

He lies, facedown, on the bed, not troubling to put a cloth over the coverlet. I pull on the brown kid gloves from the kit and take up the weapon. The blade is hideously sharp and when I slit him, the skin opens willingly. I cut from the base of the skull down almost to the arse, then tenderly tease his hide back as if flensing him. He lies still, breathing heavily, making tiny hiccups of pain. I take up one of the recently-lit candles and lean over him again and peer closely at what I’ve done.

There it is, green and healthy, throbbing, wrapped around the porcelain column of his spine, as if a snake has entwined itself, embroidered itself, in and out and around, tightly weaving through the white bones. Gwern’s blood seeps sluggishly; I slide the skean through the most exposed piece of mistletoe I can see, careful not to slice through him as well. Dropping the knife, I grasp the free end of the vine, which thrashes about, distressed at being sundered; green sticky fluid coats my gloves as I pull. I cannot say if it comes loose easily or otherwise—I have, truly, nothing with which to compare it—but Gwern howls like a wolf torn asunder, although in between his shouts he exhorts me not to stop, to finish what I’ve started.

And finally it is done. The mistletoe lying in pieces, withering and dying beside us on the bloodstained bed, while I wash Gwern down, then look around for a needle and strand of silk with which to stitch him up. Never mind, he says, and I peer closely at this ruined back once more. Already the skin is beginning to knit itself together; in places there is only a fine raised line, tinged with pink to show where he was cut. He will take nothing for the pain, says he will be well soon enough. He says I should prepare to leave, to pack whatever I cannot live without and meet him at the alder well. He says I must hurry for the doorway will stay open only so long.

I will take my notebook, the quills and inkpots Mater Friðuswith gave me, and the pounce pot Delling and Halle gifted when I entered the Citadel. I lean down, kiss him on his cool cheek, which seems somehow less substantial but is still firm beneath my lips and fingers.